Seven islands and moving pictures

The canvas that provoked India's flamboyant film culture (and its case for restoration)

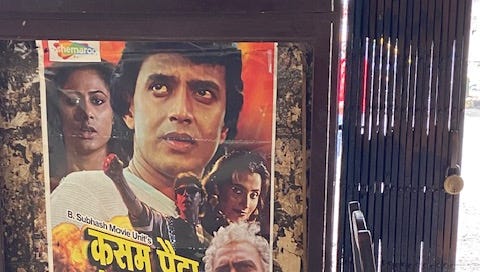

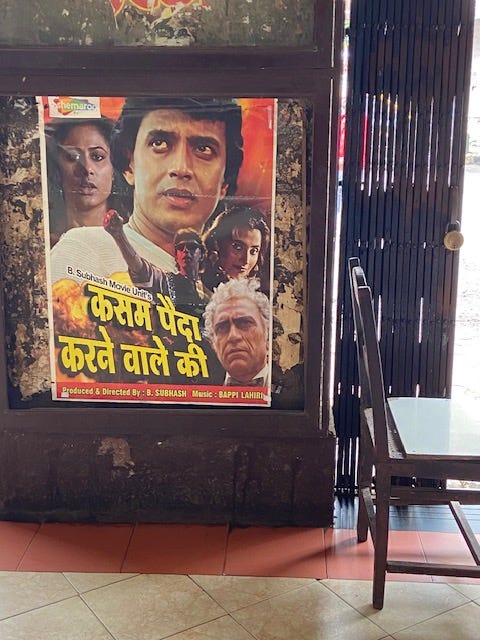

Picture: “Kasam Paida Karne Wale Ki” (1984), still pulling in the footfall at Alfred Talkies (estd: 1880 as Ripon Theatre). Snapped by the author in 2022.

Giuseppe Tornatore’s homage to the cinemagoer, “Cinema Paradiso” (1990), featured the ultimate denouement of the moving picture in a series of spliced scenes, that brought back to the main protagonist, the thrill, nostalgia and the timelessness of celluloid. The film, a classic, underlined the quaint, persistent, existence of the moving image projected on a screen, within a world where everything else has changed – the edifices of stars and reputations past, value systems, beliefs and the shared experience of a story unfolding on the silver screen. It showed us that the cinema going experience is life affirming and far from being an exercise in saving antiquity, it is a pursuit to restore the perpetuity of human endeavour - people before us who have walked their parts in the spotlight with the comprehension that they have immortalised themselves, or a part of themselves, who they were, where they were, when the cameras were rolling. For the audience, cinema has served as milestones, the images, the experience packed away like snapshots into our memories, reminding us of the time and place, the thrall, misery or mundaneness of our experience of that moment, decades later.

Coming of age in a generation that saw the final flourish before the decline of the movie going experience in single cinema halls, an imposed responsibility rests on me to translate that world for those who have grown up on fare shown in multiplexes ensconced in shopping malls. Cradled by soft lounge like seats, sozzled by a beverage and expensive pop corn, the moving images on the screen embellished by technologies such as Dolby Atmos, IMAX with Laser and 4DX, one can experience the magic of cinema in a similar way today, be it Los Angeles, New Delhi, Shanghai or Beunos Aires. How about times then, when this was not so? When we had the daily wage labourer and the technocrat breathing the same burnt tobacco and popcorn infested air to watch a cinema made for them, by a itinerant band of men scarred by partition (1947), dazzled by life in a growing metropolis and cushioned by a culture where there were a million stories from a millennia that were still be told in this ingenious format.

The Indian carpet baggers, the pioneers of our storied production houses that are still operated by their progenies, found an island, or rather a group of islands where they could tell their own stories. A story that eulogised a simpler life that they left behind, and they romanticised their coming of age in a city. The journey of the underdog. To a large extent, the audience that came to watch their wares - rooted in rags to riches, rich vs poor and beaten tracks around honour and sacrifice, were given convenient memes to latch on to - a loving mother or Ma, a crusading hero, a city bred heroine that the hero can simultaneously gaslight and serenade into becoming a demure woman. The question then arises, as to what is the redeeming potential of this fare?

The redeeming potential of a story that is told a million times over, is not the story itself. It is everything else. It is the changing milieu, the experience of cinema, the music, the ethnography, the moral dilemmas, the crumbling edifices that it leaves behind. As a nation that is continuously building over itself, a young nation in which the word “old” is a much dreaded epithet, where does the redemption and denouement a la Cinema Paradiso belong? The answer to this question begs a stubborn detour - about how the city that staged the business of making Indian movies came to be. It is like the story of a potboiler, that of an underdog, that every one in a young nation likes.

In the early 18th century, work commenced on a series of embankments and sluices to drain the swamp between the islets of Bombay, Mahim, Parel, Mazgaon, Worli, Bandra, Turbhe[1]. It was a miserable undertaking - drying up salt pans, cutting through mosquito infested mangroves, flattening high ground to fill up tidal flats.

Picture: The Mumbai city district showing the original seven islands (Gazetteer of India, 1987)

Kunbi farmers were enlisted to cultivate rice on reclaimed lands that were leased out by the East India Company. It was a loss-making endeavour as the expenses to drain the swamp were much higher than the revenue from the crop yields. However, events to unfold in the subsequent years would vindicate this huge outlay and expense, in terms of costs, bare hands, sweat and sinew.

By the19th century, ambition had soared from cultivation to settlement. As the island expanded into these reclaimed lands, Bombay became more than just an administrative centre for the East India Company. It rapidly transformed into the money capital that oiled the ambitions of an empire. The Wadias, Readymoneys, Sassoons, Jeejeebhoys and Petits oversaw a spurt in construction funded with the riches flowing in from the opium trade. Cotton futures, the opening of a Suez Canal, the establishment of textile mills, and the ongoing construction fuelled by the reclamation, drove an insatiable demand for people and resources.

Out of these erstwhile swamps rose, settlements like Tardeo and Byculla, along the Belasis Road causeway that connected the docks of Mazgaon in the east to Malabar Hill. These settlements provided the much-needed relief for the growing population. Chinese stone masons and Kamathis from Telangana were mobilised to help with the construction work. They, together with labour organised by the colonial administration, and the local Koli fishermen took over from the Kunbis, whose farms were soon being built over. The Baghdadi Jews, Portuguese and Goans (from Mahim and Bandra) Afghanis, Iranis and Marwadis together with the ruling European sahibs became the redolent and expressive heart of this new settlement that grew out of tidal flats and salt pans.

Picture: Alfred Talkies, in 2022 with its largely intact original Edwardian visage.

By the early 20th century, the streets that took the name of erstwhile Governors - Falkland, Grant, Lamington and the regional adaptation of once favoured establishments, like, the Playhouse (“Pilay House”) and Congress House, became the entertainment district within the city. In 1850, through a Governors proclamation, it was ordered that theatres be built over a graveyard in what is today the Grant Road area. The graveyard was conjoined with Mazaars of Sufi saints and through an uncanny coincidence, many of the theatres were built adjoining these tombs. Grant Road Theatre, Ripon Theatre, Edward Theatre, Victoria Theatre, Coronation Theatre, Baliwala Grant Theatre were some of the playhouses built in this area during the last quarter of the 20th century. Maurice Bandman set up the Royal Opera House for his traveling entourage, primarily for the anglo Indian population. Over time, these theatres moved on from showing plays to silent movies and talkies. Their names changed as well - Grant Road Theatre became Gulshan Talkies, Ripon Theatre became Alfred Talkies, Victoria Theatre became Taj Talkies, Coronation Theatre became Nishat Talkies. The graves of saints that once dotted

Picture: Alfred Talkies in 2022, the last few customers. The retro signage resonating like an echo from the past.

Picture: Interior of New Roshan Talkies, now closed and left to rot.

this area co-existed with these theatres, tucked away in the basement like a secret from the past. The genesis of the movie going experience, the folklore and romance behind it, would take form in these former playhouses turned movie theatres.

The “paanch ka dus”1 that landed our patron the cinema ticket. A slat of wood in the stall section, to sit on, for three hours. Three hours stolen from the bustling existence that did not seem to take our patron anywhere in life. Three hours multiplied by the many matinee, evening and night shows, seen in the company of saints and graves of common men. Moving images on screens that took the patron to places that are seldom seen or heard of. The smell of burning popcorn and beedi. The adopted language that our patron affects to belong - the “bhidu”2 who creates a “raada”3 and who delivers “kharcha pani”4 to the goons. The parvenu of a hero, the villains’ comeuppance, the happenstance ending. The exit from the theatre to the noisy world outside, the haze of the story that takes some time to fade even as worldly worries slowly pull you back to the regular moribund existence. It was a high purchased for ten rupees, but these experience shaped the consciousness of a city in which everyone was an immigrant and was running slower than the pace at which the city was growing.

The first few cinemas that were set-up in this patch of land served as template for a thousand others in the hinterland. The cubby hole of a ticket counter placed within art deco metal grilles, the sweeping staircase to the balcony, the grim imposing exterior, the flat-topped proscenium arch which housed the screen. The cinema going experience for three generations were borrowed from theatres set on a cross-section of roads that were named after erstwhile governors of Bombay. This was where it all began.

Lending these early playhouses and the latter-day theatres a racy character was the settlement of Kamathis’, Kamathipura. Criss-crossing the Falkland Road were lanes where prostitution flourished. The Kamathi women took it up first, prompted by large scale unemployment around the late nineteenth century when their men, who were construction workers, gradually began losing their jobs on reclamation projects. Soon, trafficked women from China, Japan and Europe were set up there with racially demarcated lanes like “Safed Galli”5 , a class system that even the worlds oldest profession could not escape.

Picture: Cans of theatre prints in the New Roshan talkies projection room. The then caretaker posing for the author in 2022.

European women gradually faded away after independence and were replaced by trafficked women from Nepal, Bangladesh and other Indian states.

Over time, out of these swamps grew reclaimed lands that turned into real estate gold. Breach Candy, Cuffe Parade, Napean Sea Road became glittering spectacles to the success of the metropolis, whereas other beaten parts that rose about the same time, became congested urban badlands of crime and deprivation.

Picture: Gulshan Talkies, in 2022. Established as the Grant Road Theatre in 1885. The grim concrete exterior was built over the original Edwardian frontage in the 1960s.

The hafta vasooli6 and the Dadagiri7 that the rest of India had seen in films, but had seldom experienced, came from these backwaters. The traditional Daru ka Adda8 where the villain would get drunk, came from here. It was a lived experience for the Mumbaikars in Dharavi and Sion, but for most of the cinema goers in the hinterland Mumbai was the crucible in which their onscreen heroes were shaped and received their calling.

There is nothing exalting about poverty, struggle, disease and pestilence. For a city that rose from tidal flats in a short period of 200 or so years, the only popular record of its lived experience is its moving and talking pictures, made before the onset of the internet, video piracy and the age of social media addicted micro attention span world. The picture palaces where these films once ruled and drew in patrons, are in tatters today. Some of them are parking lots, others stand as mute spectators to time passing by, awaiting their eventual demise. Still others continue to operate as before, running recycled, decade old films and cranking out the last runs of celluloid in a world that has moved on, decades ago. The red-light district is muted. The tea shops still offer cutting “chai” and if you linger long enough, the shop owner will tell you a few stories about how things used to be.

Picture: The temperature-controlled storage within the NFAI, where films are carefully restored and digitised for posterity under the discerning eyes of archivists.

The lived experience or its dramatised ersatz counterpart does not exist today in the celluloid form, unless it has been rescued. Many such artefacts still lie as exposed theatre prints in the projection rooms of moribund theatres. Organisations like the National Film Archive of India (NFAI), in Pune, diligently pursue camera negatives through their exist contacts with production houses. Yet, many have been lost. The ones that do make it to the NFAI, are painstakingly restored by expert archivists like Leenali Khairnar and her team at NFAI.

The walk from Falkland Road to New Roshan talkies is a short one. No one grudged the resident of the brothel, a Kamathi who stole three hours from her existence to enjoy a predictable story on screen. It is less about that story, and more about the fact that for those three hours, in that dark cinema, she is auteur of her own script, that interweaves with that potboiler. It is a luxury that is not affordable for millions of Indians today, in the age of the multi-plex and dopamine fueled world of social media. What can be salvaged from the crumbling edifices and the archives today could also be our own stories, as they could have been.

Literal translation is “5 in 10”. Black marketeers would often bulk buy tickets for popular films well in advance and sell it for twice the price to desperate patrons once the “Housefull” boards were put up i.e; A tickets costing Rupees 5 for Rupees 10. The practice stopped with the on coming of the multi-plex era. It has been enacted in a number of movies from the 1970s to the 1990s.

Derived from card games and deployed on the street. A partner or a chum.

Trouble at a smaller scale. Like a fight or an altercation.

The Hindi translation is “pocket money and water”. The laconic colloquial translation is “to beat up” or “rough-up” or worse. You get the drift.

“White lane” is the literal meaning.

Extortion or protection money was levied from business owners and shop keepers by the local toughie, usually on behalf of an organised cartel. In most popular depictions, such goons were usually beaten by by the Hero or leading character, as his introduction to the audience.

The practice of conducting a series of illicit businesses in the neighborhood. Extortion, gambling, black marketing in the 70s changed to running beer bars, night clubs, drugs, arms and prostitution in the 80s and 90s. Again, documented in a number of potboilers of that time.

Illicit arrack and hooch joints were a prominently featured in movies. The underdog hero, usually gained his spurs by beating up toughies at such joints. Filmography reflected the dark reality of prohibition in slums (post independence) where the underworld provided patronage and protection to such joints.